Minimmit: Simple and fast consensus

Minimmit 1 is a recently proposed blockchain consensus algorithm by Commonware. It falls into the new class of consensus protocols that require more than 80% of participants to be honest (rather than 2/3rds as in traditional asynchronous BFT protocols); in return, you get a lower latency protocol that achieves consensus after only one round of voting (this is called 2 rounds because the block proposal by the leader counts as the first round).

What I like about it is that it feels like a consensus algorithm properly designed for blockchain protocols: Leader rotation with chained proposals is integrated into the protocol rather than bolted on as an afterthought. This achieves a beautiful simplicity that has a cleaner feel than many traditional BFT algorithms. The separation of justification and finalization is one of the most difficult things to understand when first approaching BFT literature; and full leader rotation in the case of leader failure is often horribly complicated and incompletely described in papers and buggy in implementations. In Minimmit, it feels much more natural (assuming that you are coming from a blockchain context).

Quick notes on this article

My goal here is mostly to give an intuition for how Minimmit works and why it needs an 80% majority. Whenever I write 2/3rds majority, or 80% majority, it should be read as saying as requiring one extra vote, so 2 out of 3 is not enough to satisfy a 2/3rd majority but 3 out of 4 is and 7 out of 10 is.

The intuition of why an 80% majority is needed

If you want to finalize with a single round of voting, you need 80% of nodes to be honest: formally Minimmit uses \(n \geq 5f+1\), where \(n\) is the total number of nodes and \(f\) the number of byzantine failures tolerated, i.e. the number of nodes that can behave completely adversarially. This means strictly more than 80% of nodes need to be honest. The general tight lower bound for fast Byzantine consensus is actually \(n \geq 5f-1\) 2, which applies when proposers are a subset of acceptors. However, FaB Paxos 3 established that \(n \geq 5f+1\) is necessary for a specific class of protocols where proposers and acceptors are distinct sets. For a recent treatment in the blockchain context see Minimmit 1.

A good way to understand why this is necessary is to understand that the leader, i.e. the block proposer, can be byzantine, and one of the things they can do is to propose several blocks at the same time, so honest nodes disagree on what to vote for. What we want to avoid is the leader being able to put the protocol into any bad state; the worst case would be finalizing two incompatible blocks (blocks that aren’t in the same chain), but we also can’t allow them to put the protocol into an unrecoverable state (i.e. a state where the protocol can’t automatically recover without manual intervention).

Here is an intuition why 2/3rds majority can’t do one round finalization. Assume we finalize a block if it gets 2/3rds of the votes. Let’s start with the easy part: An honest proposer proposes exactly one block. All honest nodes will vote for this. In a partially synchronous network all votes will eventually arrive at all the honest parties, so they will all see that 2/3rds have voted for the block. So far, so good.

However now we have to think about a malicious proposer. One thing they can do is not propose a block. The protocol needs to be able to detect this, so parties have to be able to vote for an empty slot (in Minimmit this is called nullify, so I will call it nullifying from here onward). If 2/3rds of the nodes vote to nullify the block, we can move on.

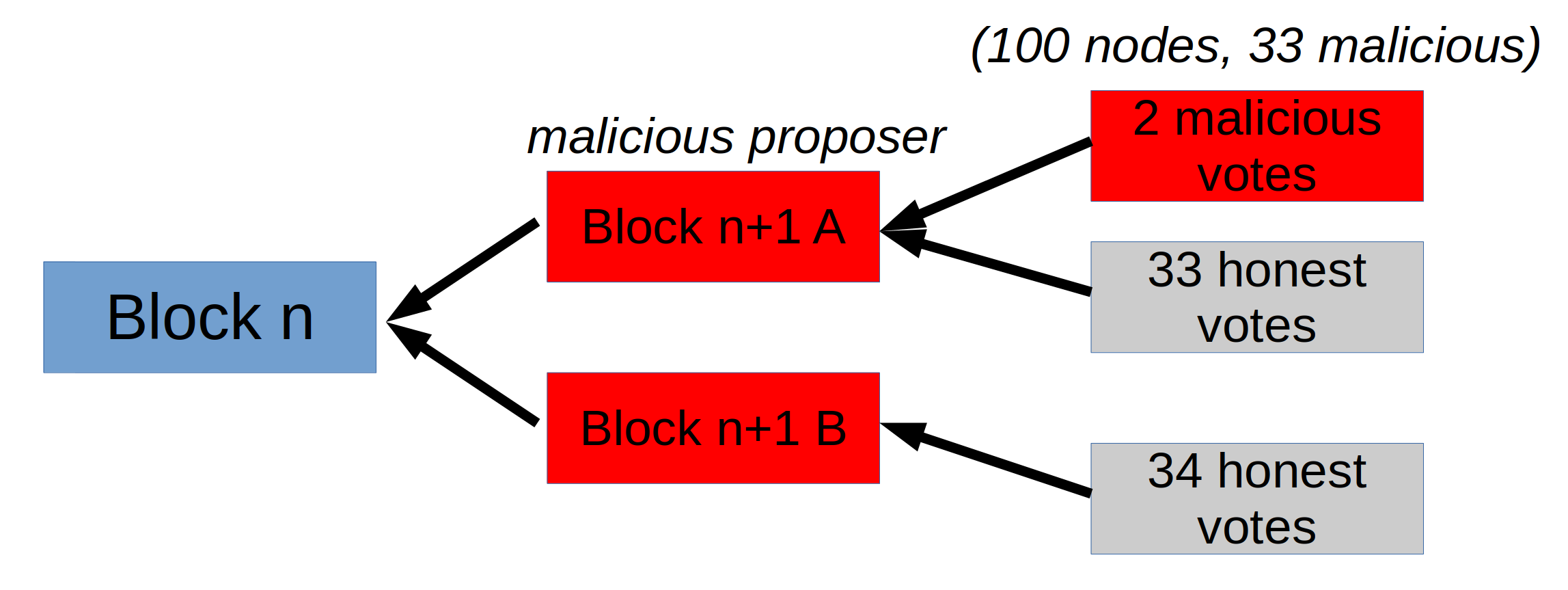

But unfortunately, the leader can do worse than just not proposing a block: They can also propose two different blocks at the same time. Now we will have a situation where about half the honest nodes vote for each proposal. In addition we have to remember that malicious nodes can vote twice, or not at all, or even withhold their votes until a later time to decide their action after seeing what the honest nodes are doing. Here they could temporarily lend some votes to the proposal with fewer votes to have it appear to have the majority of votes, like this:

If the protocol uses the option with more votes to continue the chain it means that the next round is started on an unsound building block, because the malicious nodes would have the power to finalize the other option. The protocol designer faces an impossible choice:

If the protocol uses the option with more votes to continue the chain it means that the next round is started on an unsound building block, because the malicious nodes would have the power to finalize the other option. The protocol designer faces an impossible choice:

- Never continue until a proposal reaches 2/3rds of votes. In this case, the malicious proposer can stop the chain

- Continue with whichever proposal reaches the most votes. In this case, the malicious nodes may be able to finalize a different proposal with their remaining votes or by equivocating

This is the conundrum that traditional BFT algorithms solve with justification. The first round of voting is to justify a block (which cements that it was properly proposed by a non-equivocating proposer). When a block has been justified (i.e., when f+1 correct nodes have seen a quorum of first-round votes in a timely fashion), honest nodes cannot vote for incompatible blocks in later views in protocols like PBFT 4. But this adds an extra round, which is what we want to avoid here.

This is the intuitive explanation why we can’t finalize with a 2/3rds majority in a single round.

Why it works with an 80% majority:

Let’s change this, and require a greater than 80% (4/5ths) majority to finalize. As before, we don’t need to worry about the case where there’s an honest proposer.

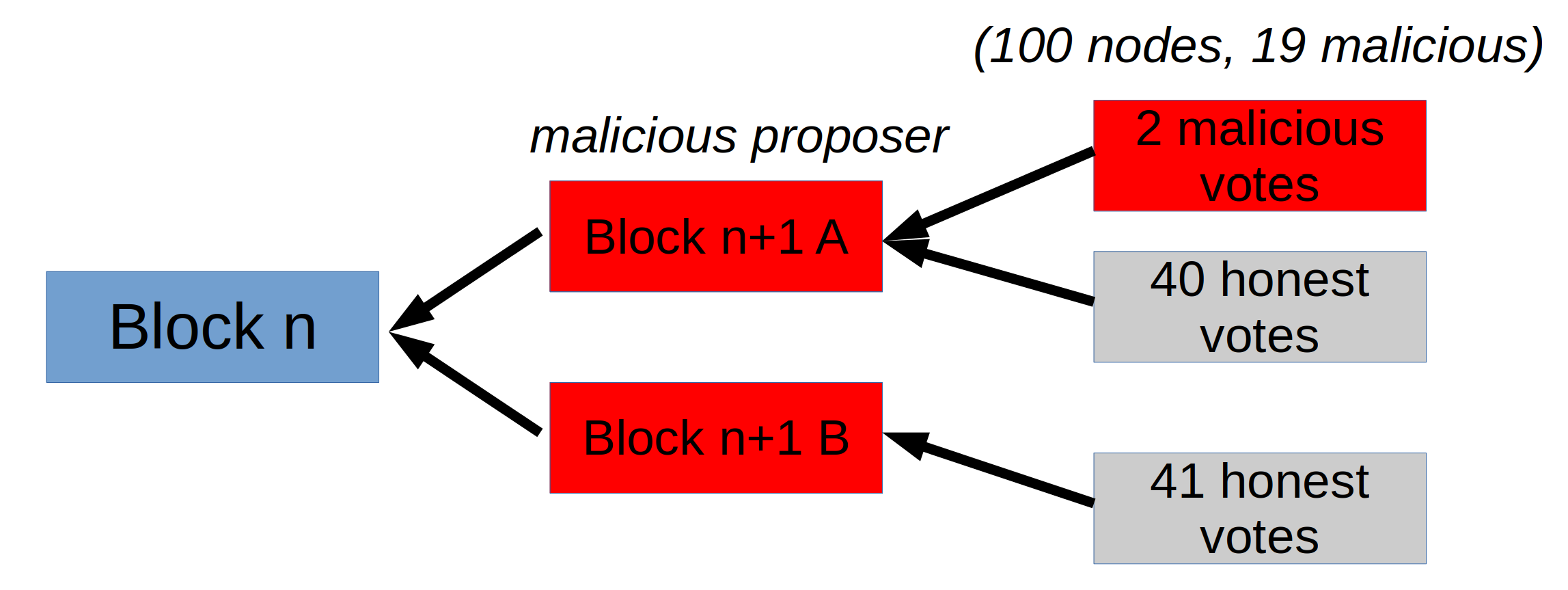

Instead let’s look at the case where the proposer splits honest nodes. Let’s say we have the honest nodes about equally split between the two different proposals:

Note an important difference now: The malicious nodes no longer hold the power to finalize either of the two. Adding their votes only gets them to 60% and not to 80%. This is good: It means we can move on with one of these options without risking that the other will be finalized, which would be bad. This lets us formulate more clearly what we want:

- We need the next proposer to be able to infer a safe block to build on – or an empty (nullified) one. What we want is that if they are honest, their block will be finalized (and this can’t be contradicted by a conflicting block from the previous round being finalized)

Minimmit does this using an M-notarization (M for mini), which is a set of more than 40% votes (or nullify votes). The important thing is that an M-notarization is not a finalization (called L-notarization in Minimmit, though I will just call it finalization). That’s because there can be several M-notarizations in the same slot. The best way to think is that it’s a signal by the protocol to the next proposer: “It’s safe to build on this block”:

- It means in the slot of the M-notarization, no other proposal can be finalized

- If an honest proposer builds on an M-notarized proposal (or nullification), then their block will be finalized; in other words, if the next proposer (a) proposes on time and (b) does not equivocate then their proposal will be finalized

The tricky part is now making sure that there always is an M-notarization for each slot; when there are only two options like in my constructed example, this is ok; but what if the proposer sends many different blocks, so there are now more options and none of them gets more than 40% of votes? This is solved by instructing honest nodes to also send a nullify message if they have already voted, but only if they have seen more than 40% votes that are either nullify votes or votes for a block that they didn’t vote for. This is safe because that condition means that the block they voted for can’t be finalized anymore; so they can safely vote to nullify this slot.

This idea is very cool, because it makes the protocol super simple: No special view change algorithms other than the one that is already built into the blockchain. And it’s also doubly fast: It can progress with only 40% of votes, and it can finalize after only one round of voting (with 80%) of votes coming in.

Now, let’s get back to the part why we need specifically more than 80% honest nodes, and not some smaller fraction like 75% (we have already seen that 2/3 is not enough). The key property we have used is that if an M-notarized proposal exists, then no other proposal can get finalized in the given round. Now, 20% of that could be the malicious nodes, so we really only know that more than 20% honest nodes have voted for this proposal. This means another just under 60% of the honest nodes could have voted for a different proposal. This is key: with the malicious nodes double voting for the second proposal, it can still only get to just under 80%, not enough to bring it over the edge and finalize it.

This being very close to the finalization threshold of 80% prevents us from lowering the honesty requirement. If we allowed 21% malicious nodes, the math wouldn’t work out: We now require 79% of votes to finalize (need to be able to finalize without the help of malicious nodes), and we would have to require \(100\% - 79\% + 21\% = 42\%\) to M-notarize. We also need to increase the threshold to send a nullify vote after already voting (the key to moving on with malicious proposers who do multiple proposals) to 42%. Now let’s say the malicious proposer sends two blocks, and the malicious votes don’t vote; there is a possibility they each get 39% of the honest votes. The protocol is now stuck: Neither side of the split votes would be able to nullify their votes, because they can’t see 42% votes for something else (only 39% are on the other side). This shows intuitively why we can only tolerate less than 20% nodes malicious with this protocol.

Description of the protocol

We are ready to give a description of the protocol. We assume a schedule of leaders pre-determined in another way (this is typically given in blockchain protocols, for example they can use a VRF (verifiable random function) to determine a random leader or simply rotate through all nodes).

Definitions:

- A proposal is a block signed by the proposer of the current round. A block also refers to its ancestor, thus creating a chain of blocks.

- A vote is a message signed by a node that includes a hash of the proposal being voted for. It is signed by the voting node

- A nullify message is an alternative vote that says there was no valid proposal, or there are several valid proposals in this round. It only includes the round number and the node signature

- An M-notarization is a collection of more than 40% of the votes for a valid proposal; more than 40% of valid nullify messages for the current round are called a nullification

- A finalization is a collection of more than 80% of votes for a valid proposal

- A proposal is valid if it is a descendant of the last finalized block, all ancestors since the last finalized blocks are M-notarized or valid nullifications, and it bears the signature of the round leader (the blockchain protocol can add additional validity conditions)

In each round:

- The leader waits until they see an M-notarization for a valid proposal in the previous round (or a nullification)

- They propose a block based on this

- All nodes vote for the valid proposal that they see first, or to nullify if they don’t see a proposal within a time specified by the protocol

- If a node sees 40% of votes that are not for the proposal it voted for, it also votes to nullify the round.

- Nodes advance to the next round as soon as they see an M-notarization for the current round.

The key is that for each round:

- There is always an M-notarization or a nullification (so the protocol can always progress)

- If there are several options (several M-notarized proposals or an M-notarized proposal and a nullification), then none of these options can be finalized (this means it’s always safe to build on an M-notarization of a nullification)

Is M-notarization similar to dynamic availability?

In Ethereum, the idea of “dynamic availability” is that we can continue building a chain even if less than the consensus majority (in Ethereum’s case, 2/3rds) are online – this dynamically available chain is not safe against reorgs like a finalized chain, although it does provide some guarantees against minority attackers.

Assuming all online nodes are honest and under reasonable synchrony assumptions, Minimmit can build a chain with only 40% of nodes being online, similar to a dynamically available consensus. While it requires 40% of nodes being online (compared to being able to continue even with single-digit percentages in Ethereum), it’s still much better than most BFT protocols which fail as soon as fewer than 2/3rds of all nodes are online. It looks similar to ebb and flow constructions or Ethereum’s FFG+GHOST construction.

Let’s consider what happens when two different chains of M-notarizations are available, which can occur after a network partition. Suppose we have a partition where two sets of nodes (each with sufficient nodes to form M-notarizations) operate independently, with synchrony maintained within each partition but no communication between them. Since Minimmit doesn’t use fixed slot times but instead advances rounds when M-notarizations are seen, the two chains will likely advance at different rates, resulting in different round numbers.

When the partition is resolved and synchrony is restored, the next honest leader (assuming leaders are randomly selected and unknown to the adversary in advance) will see both chains. They can choose which chain to build on, and all honest nodes will vote for their proposal. However, if one chain has reached a higher round number (i.e., has more M-notarized rounds, not counting nullifications), then nodes following the shorter chain will have already advanced to match the longer chain’s round number as they see the missing M-notarizations. In this case, the leader has no choice but to build on the chain with the higher round number, so the partition resolves in favor of the chain that advanced faster.

This is not unlike Ethereum, where proposer boost 5 had to be added in order to ensure that chain splits can always be resolved in the presence of an attacker who tries to balance the chains (adds their vote to always keep the votes split). In Minimmit, when chains have similar round numbers, the proposer acts as the arbiter; but when one chain is clearly longer (in terms of round numbers with M-notarizations), the protocol naturally favors it.

References

-

Chou, B. K., Lewis-Pye, A., & O’Grady, P. (2025). Minimmit: Fast Finality with Even Faster Blocks. Accepted to FC’26 (Financial Cryptography 2026). ↩ ↩2

-

Kuznetsov, P., Tonkikh, A., & Zhang, Y. X. (2021). Revisiting Optimal Resilience of Fast Byzantine Consensus. The authors show that \(5f-1\) is the tight lower bound for fast Byzantine consensus when proposers are a subset of acceptors, correcting earlier misconceptions. ↩

-

Martin, J. P., & Alvisi, L. (2006). Fast Byzantine Consensus. IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing, 3(3), 202-215. FaB Paxos established that at least 5f+1 replicas are necessary for two-step consensus protocols where proposers and acceptors are distinct sets. ↩

-

Castro, M., & Liskov, B. (1999). Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance. In OSDI (Vol. 99, pp. 173-186). In PBFT, once a request is prepared (justified) in the prepare phase, honest replicas will not prepare conflicting requests in the same view. ↩

-

Proposer boost was introduced to prevent balancing attacks in Ethereum’s fork choice. The mechanism is specified in the Ethereum consensus specifications and was discussed in the context of LMD GHOST fork choice. For the original discussion of balancing attacks and the need for proposer boost, see ethresear.ch discussions. ↩