On supply and demand for stablecoins

Special thanks to David Andolfatto, Vitalik Buterin, Chih-Cheng Liang, Barnabé Monnot and Danny Ryan for comments that helped me improve this essay

The value of a freely tradable asset is determined by supply and demand. This obviously applies to stocks and cryptocurrencies. But it also applies to any “stablecoin” we are trying to create. It even applies to traditional fiat currencies like the US Dollar or the Euro.

When I talk about stablecoins here, I am referring to decentralized, collateralized stablecoins like MakerDAO’s DAI – not to USDT or USDC, where the supply/demand problem is obvious. So how does MakerDAO balance supply and demand for stablecoins?

And how does this help us learn how central banks do this for fiat currencies?

How to create a stablecoin

Let’s understand how we can create a stablecoin if as a building block we only have assets which are subject to undesirably large volatility. Luckily we have a great example on how to do this by means of collateralized stablecoins, the prime example of which is MakerDAO, the project behind the DAI stablecoin.

The idea behind this project is to create a token, called DAI, that tracks the value of one USD as closely as possible. Note that instead of using USD, we can track any other asset as well – RAI, as an example, tracks a time-averaged version of the Ether price. I suggest that long-term, the Ethereum community should strive to create an Oracle that tracks the prices of consumer goods in Ether, so that we can create a stablecoin that has nothing to do with any currently existing fiat currency and is thus truly global and independent. But as a starting point, using USD which is a denomination that most of the world understands intuitively as relatively stable was probably a very good idea.

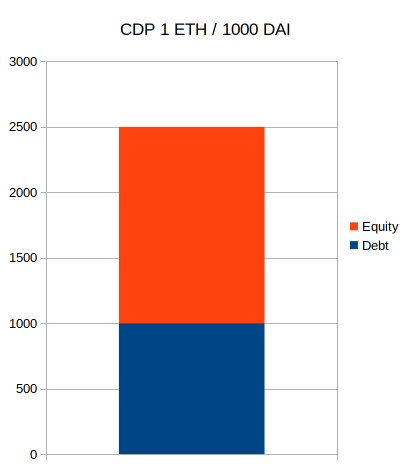

How did MakerDAO manage to create this stablecoin, without any cash reserves in the form of bank accounts in USD and only the on-chain assets, which are all highly volatile? The core idea is the so-called Collateralized Debt Position, or CDP. It’s a margin position where someone can lock up a volatile asset – for example Ether – and in return create, or “borrow”, a number of DAI. The CDP essentially splits the value of the locked up Ether into two tranches:

- The first tranche is the “debt tranche” – this tranche is fixed in its USD value and belongs to whoever owns the actual DAI stablecoins

- The second tranche is the equity tranche – it belongs to the owner of the CDP and is the value that is left once the first tranche is satisfied

Notice I called them “debt” and “equity” here, because that’s the way we call them when we talk about companies doing the same thing: When companies need capital, they can raise “debt” – in the form of bank loans and bonds, typically – which is very predictable and gets preference (as in is paid back first using the remaining assets) when the company runs out of money. That’s why bonds (which are tradable debt) are quite stable in price: As long as the company doesn’t go bust, they will always be paid back. Equity is the value that’s left over once these debt positions are satisfied, and is traded in the form of stocks – which are much more volatile, because their value depends on the profitability of the company, not just its solvency.

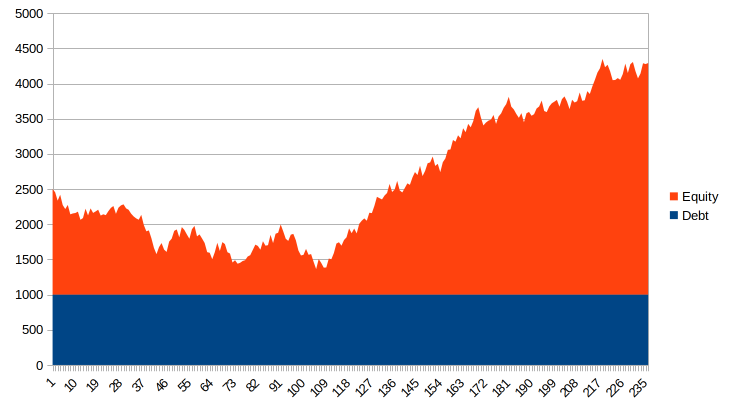

The elegance of this system is that the equity position can absorb the volatility, so that the debt holder (which is whoever holds the DAI thus created) has a predictable value. As an illustration here, see what happens when the value of the 1 ETH that has been locked up in the above CDP fluctuates:

The equity holder gets a position that’s now highly volatile (and in return, if the value of ETH goes up, will get much enhanced returns). The “debt” part of the CDP stays nice and constant and is always worth 1000 USD, as long as the ETH price does not crash too rapidly.

The equity holder gets a position that’s now highly volatile (and in return, if the value of ETH goes up, will get much enhanced returns). The “debt” part of the CDP stays nice and constant and is always worth 1000 USD, as long as the ETH price does not crash too rapidly.

This last part may look scary as if the red “equity” part of the line ever goes to the $1,000 line, the DAI debt could suddenly not be satisfied and thus the value of one DAI would fall below one USD. However, MakerDAO will actually liquidate CDP positions once they get too close to zero equity. This works by auctioning off the collateral to the highest bidder in DAI.

This means that in practice, MakerDAO can deal with extreme falls if they do not happen too rapidly; this has been tested repeatedly, for example in March 2020 when DAI held its peg despite a precipitous fall in crypto asset values.

(This largely describes the old version of DAI, single-collateral DAI (which only accepted ETH as collateral). The current instantiation, multi-collateral DAI, differs in that it also accepts other forms of collateral (which is great), some of which are centralized stablecoins (such as USDC) which is not so good in my opinion.)

Why we need to add interest rates to this

MakerDAO has a simple mechanism to make sure the long-term expected value of DAI should be one USD: In the case of a large deviation, the governance system can trigger global settlement, which will immediately give all DAI holders their current equivalent in ETH by tapping all the CDPs that secure it. However, this event can be far in the future and thus doesn’t guarantee that the instantaneous price is exactly one DAI.

Let us understand the goal that MakerDAO has with DAI: They want 1 DAI to always be worth 1 USD.

One might think: Oh but it would be ok if it sometimes is more than 1 USD right? As a matter of fact, this is also bad: If it costs more than 1 USD to get 1 DAI, then MakerDAO would have failed. Because if I can only get a DAI for 1.10 USD then it means it doesn’t act as a stablecoin for me – it can suddenly fall by 10% and I will lose that value when it goes back to its intended peg of 1 USD. It’s thus essential that the peg is always kept in both directions.

But like any freely traded asset, the value of DAI is determined by supply and demand.

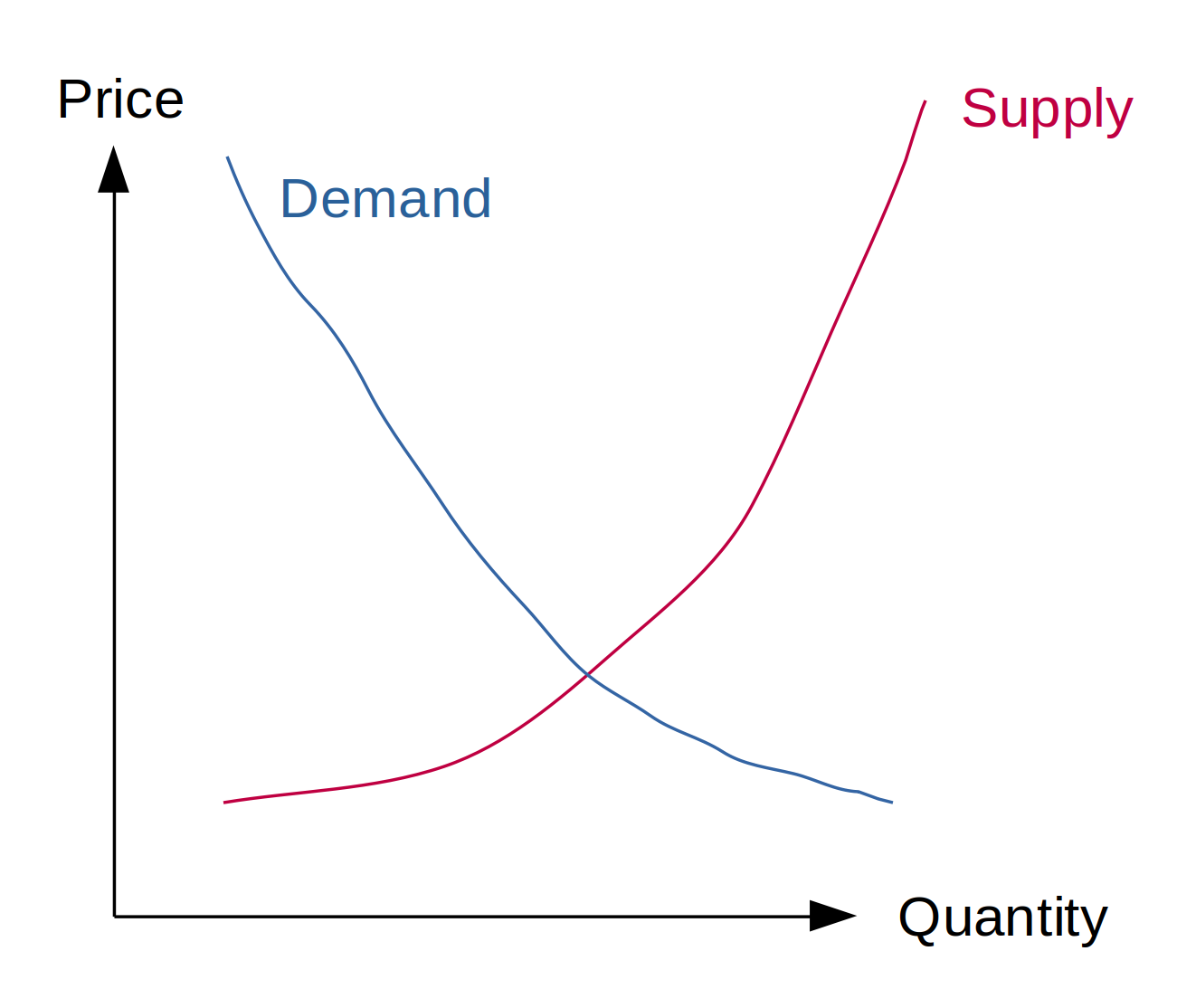

What does it mean for a price to be determined by supply and demand? Let’s say we’re talking about a commodity like wheat with many independent buyers and sellers. The buyers of wheat follow a certain “demand curve”: The higher the price of wheat, the lower the quantity demanded; this is intuitively easy to see: if wheat becomes really expensive I will buy rice instead of flour. If wheat becomes crazy cheap then I will substitute other foods by using more wheat or even buy a few extra bags just in case I need it later. The behaviour of many consumers in aggregate makes this a smooth curve.

The supply curve looks at the other side, the producers of wheat who want to sell it into the market. The suppliers are farmers who grow wheat. They make a similar decision based on the current market price. If the price is low, they won’t grow wheat, or potentially put some of it in storage to sell later at a higher price. If the price is high, they can replace other crops with wheat or even grow it on fields that aren’t currently worthwhile because the yield is lower or it’s harder to harvest.

Conceptually the two curves can be drawn into a graph like this:

Economists traditionally put price on the \(y\)-axis (vertical) in this graph, when as the independent variable it would usually be on the \(x\)-axis (horizontal).

There is a price at which both curves meet. In equilibrium, this is the expected price for the commodity if there isn’t any interference with the market. This is because if the price is lower, then not all demand can be satisfied, so producers will notice they can be more profitable by increasing their prices, thus raising the overall price. On the other hand, if the current price is higher, then there will be too much supply fighting for the few consumers wanting to buy wheat, and thus the producers who lower their prices will be the ones making a profit (or a lower loss) as the consumers will be turning to them. The only stable point is where the two curves meet.

The same applies to DAI – which can be traded freely on exchanges.

Supply of DAI is given by those people who are happy to take a CDP position, which basically means leveraging their volatile assets, in order to create more DAI, as well as anyone already holding DAI and wanting to sell. Demand comes from those who want the stability of keeping their value in DAI.

These two curves don’t necessarily meet at a price of one USD per DAI.

As an example, if the market for Ether is very bullish and many people think it will go up, then it probably means that there is little demand for the stability that holding DAI provides and a high demand for leveraged Ether positions. People who are very bullish on Ether would be tempted to leverage their positions to profit even more when the price increases. In this kind of environment, so many people want to take out CDPs and create DAI that there are not enough people interested in actualling using all the DAI. The value of DAI would fall below the peg, which is undesirable.

MakerDAO can correct this by adding a positive interest rate (“savings rate”) for holding DAI, rewarding the holders and charging those who take the margin position. This makes it more attractive to hold DAI. You may think ETH is a great investment, but it’s volatile, so maybe DAI with a 5% savings interest would seem attractive. If it’s not 5%, then maybe 10% is. At some value for this interest rate, the demand for DAI will increase enough (and the supply in form of CDP decrease enough) such that the value of DAI will return to the intended peg.

But the reverse is also possible – in an environment where many people prefer the stability (maybe in a “bear market” where holding Ether isn’t as attractive), a negative interest rate makes holding DAI less attractive and thus reduces the demand. On the other hand, taking out a CDP becomes more attractive when you actually get paid for it. You may be scared of taking out a 1000$ loan against your ETH, but what if you got paid 10% or 100$ per year for it?

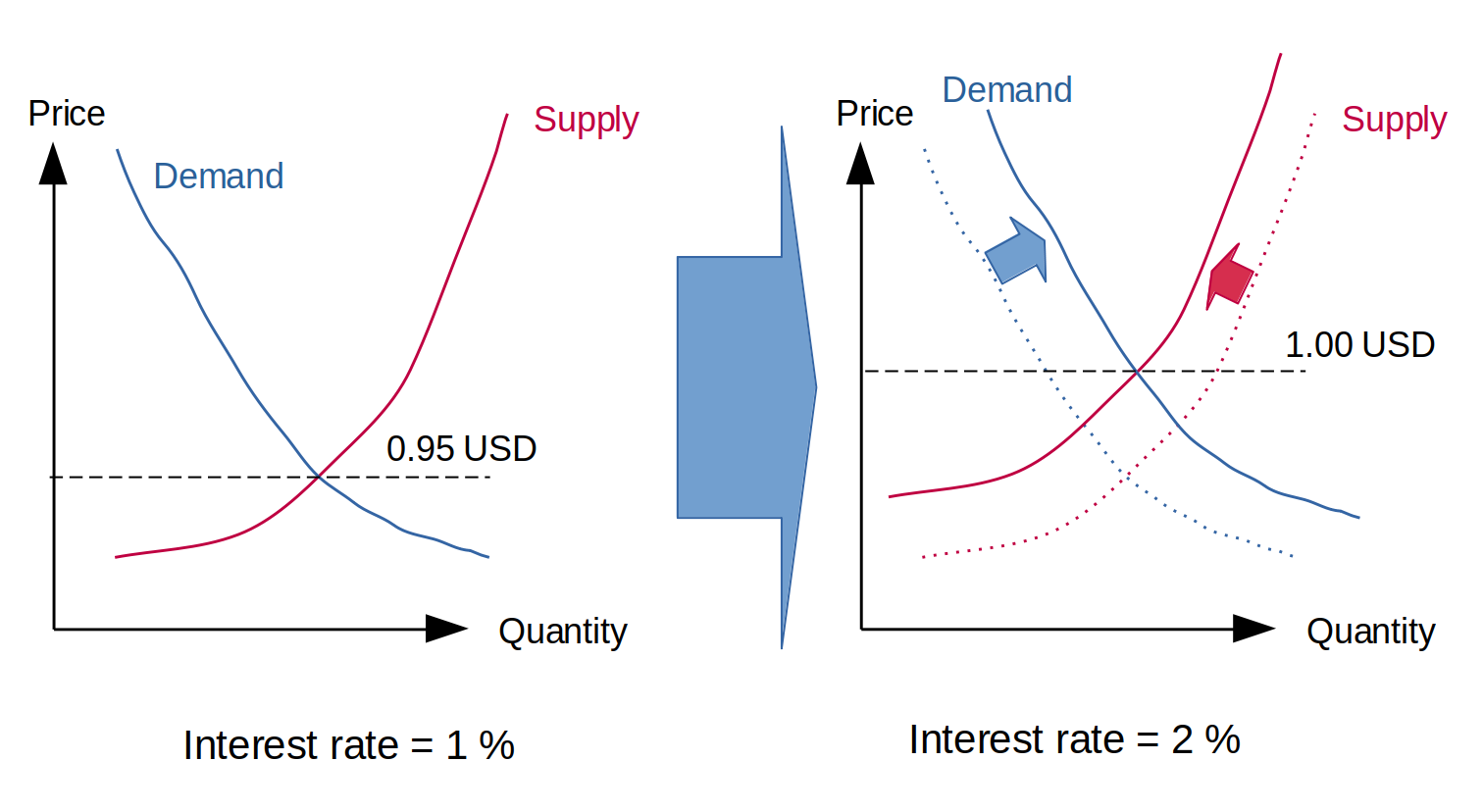

So we now effectively have another dimension in order to change supply and demand for DAI – the savings interest rate. A lower rate (even negative) rate will decrease demand and increase supply, leading to a lower DAI price. A higher rate does the opposite and increases the price of DAI. In order to move the price to 1 USD, we just have to adjust the interest rate until the prices agree.

Here is a graphic that illustrates how this works:

On the left, we have supply and demand curves at an interest rate of 1%. The curves meet at a price of 0.95 USD, which is the current fair market price of DAI and thus too low. In this situation MakerDAO would need to raise the interest rate. By raising the interest to 2% (on the right), the CDPs become less attractive (shifting supply) and holding DAI becomes more attractive, thus making the curves meet at the desired price 1.00 USD.

In the light of this, I am very happy that MakerDAO has after a long time decided to implement the ability to support negative interest rates. They are essential when a lot of stability is demanded. In fact, not having this in the past has required the very unfortunate decision to use centralized stablecoins such as USDC to back DAI, otherwise the demand could not have been satisfied and it would have shot above the peg. Hopefully, long term, this will be reversed.

To summarize, the interest rate is a mechanism that balances the demand and supply of the stablecoin. An ideal system should simply pick a rate that equates supply and demand – this interest rate would represent the fair market price for keeping value stable. Depending on the overall economic situation, this interest rate can be either positive or negative.

An analogy to fiat currencies

“Fiat” currency is actually a huge misnomer for our state currencies. “Fiat” implies that someone just creates a large amount of (what we in the cryptocurrency ecosystem would call) tokens and – by “fiat” (latin “let it be done”) – tells everyone that this is now money.

However this is not really how fiat currency works. Fiat currencies are actually to some extent “collateralized stablecoins” as described above, with some extra complications. As many commenters have noted in the past, we should be calling them “credit currencies” instead.

To see this, we need to understand that traditional money consists of two different components (there are more but these two will give the idea how it works):

- Central bank money, which consists of reserve accounts (that banks have with the central bank) as well as all the physical money (bills, coins) in circulation; this is often denoted M0 (and can properly be called “fiat” currency)

- Bank deposits, which is basically the money you have in your bank account, and similar liquid deposits. This is called M1.

But what actually is M1 money? It’s nothing else but “debt” that your bank owes you. This debt is often created by someone taking out a loan from the bank: E.g. when you take a mortgage, two accounts are created: One that says “bank owes you money” and the other one “you owe the bank money” and they cancel each other out. Your bank’s net position hasn’t changed, although it has become riskier (more leveraged) through the process. And new deposits have been created, thus enlarging the M1 quantity.

But that mortage is backed – collateralized – by both your income and the property it’s taken out for. In effect, each loan a bank gives out is very similar to our collateralized debt position above. When you take out your mortgage for 200,000 USD, your CDP is:

- You are long 1 house

- You are short 200,000 USD

Now it looks much more like a CDP. While central banks and states have other tools to change supply and control inflation, this debt mechanism is a powerful constraint that can dynamically adjust the quantity while keeping the value of the currency more or less unchanged.

So are negative rates and inflation not a scam?

As we have seen previously, DAI sometimes needs negative interest rates to maintain the peg. In the wake of the financial crisis of 2008, people were surprised that interest rates on bank accounts, and indeed even central bank interests, can be negative. But is this really that surprising?

Central banks have more than a single lever to adjust supply and demand for their currencies, but interest rates are still an important one. Negative interest rates send a signal to the market that rebalances the equilibrium towards lower demand for stable currency and higher supply by means of people taking debt in order to invest it in ventures.

Furthermore, inflation is basically a negative interest rate on physical cash (bills and coins), which is necessary because we don’t have any way of applying it directly. If all balances were electronic, we could equivalently also just apply the negative interest rates directly to the balances and not have any inflation. (This ignores price stickiness, which is another problem that probably also favors some form of inflation)

Conclusion

MakerDAO has demonstrated that even if you only have a volatile asset, like ETH, you can build a stable currency on top. For simplicity, a peg to the US Dollar was chosen, but it doesn’t have to be a currency. Any measure of value could be used, as long as we have a way to find a reasonably objective oracle for it.

I don’t believe that assets that are only defined by their limited supply – such as gold or Bitcoin – are very good “stores of value”. Historically speaking, the S&P 500 has vastly outperformed gold 1 at lower volatility. I don’t think this will be different for Bitcoin and other “limited supply” assets. If what you want to do is maximize value over long timescale, productive assets (which Ethereum will be after EIP1559 and the merge) are a much better bet.

If instead you want stability over short term, you need an explicit mechanism that guarantees that; stablecoins are one, and fiat has similar mechanism. But someone will have to take the other side, and you will probably have to pay for it by having lower or even negative returns. That’s the price for stability.

You can also do something in between, like Reflexer Labs RAI. What I don’t see is how gold or Bitcoin, simply by having a fixed supply, provide something superior. They don’t. They will be strictly inferior by providing less returns at higher volatility than productive assets and the stable synthetics we can build using them. I wrote an essay about this topic: Just because it has a fixed supply doesn’t make it a good store of value

–

-

Starting in 1950, investing $35 in gold (one ounce) would have yielded $1765 (price as of June 20 2021 from here) vs $74,418.65 for investing in an S&P 500 tracker. Both yield positive returns even after accounting for the ca. 90% inflation of the USD, but the S&P 500 is much better at 212x real returns vs only 5x for gold. Also gold is more volatile than stocks. ↩